It seems that the whole world sees a positive spread between cap rates and interest rates as required for a real-estate investment to make sense. The thing is, this is just plain wrong.

Certainly if you are a private-equity firm and you seek to invest the funds from your investors at 70% leverage, then you had better find positive spreads. (Well, in the absence of persistent inflation — see below). But still, knowing the spread tells you nothing about how profitable the investment will be.

And in the markets today, we are seeing things happen for which that spread-based paradigm is deeply misleading. This is particularly true for individuals and publicly listed REITs. Even so, various sell-side analysts and other idiots keep pumping out incorrect stories.

Spread-based investing in real estate, as a theme, did not emerge until the 1990s, when interest rates dropped sufficiently below cap rates. It has become progressively incomplete in this century.

This is especially true lately, as the spread between cap rates and treasury rates has narrowed. Let’s look at some reality.

Cash Cares Not About Spreads

We have been seeing an increasing amount of real estate investing with cash, supplemented by little or no debt. For net-lease properties, Globe Street recently offered these comments.

[From Matthew Mousavi, Managing Principal at SRS Capital Markets:] “The fact that we’re still transacting net lease, at cap rates well below interest rates, to all cash and negative leveraged buyers is a clear indication that net lease remains in strong demand. Investors, and all the sidelined capital, are still hungry for deals. As the market stabilizes on rates and valuations, we expect transactional activity to pick up in 2024.”

According to Andrew Fallon, Executive Managing Director and Market Leader, “Most active buyers are focused on acquiring best-in-class credit tenants, well-located assets with strong real estate fundamentals, and they are willing to pay a premium. Our weighted average cap rate for Mid-Atlantic net lease assets was sub 6% at 5.68% for Q1 2024. Many of these deals were long-term corporate ground leases and/or newly QSRs, C-Stores and necessity retail with investment grade credit.”

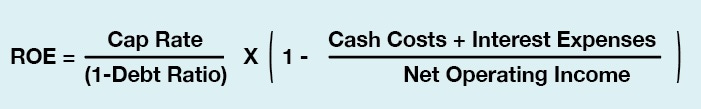

Why can this work? Well the Return on Equity (ROE) for a new cash investment is related to cash cap rate, debt ratio, and interest rates as follows:

You can see that debt has two effects. It leverages up the cap rate and it increases interest expenses. The spread as such does not directly matter, but does have consequences seen below.

So what returns does one get? Consider properties under net leases.

The property lease is assumed to be a triple-net lease, where the tenant has responsibility for all maintenance, taxes, and insurance. One has very low other expenses from such a lease, here taken to be 5% of Net Operating Income (NOI).

With zero debt, buying a property with a 6% cap rate and those costs gets you a 5.7% ROE. That is not bad, and remember that the income will endure no matter what happens next with interest rates. The lease will have some escalator and a well-chosen property is likely to increase in value with time.

So if you have cash you can get that ROE by investing it. There is no cost of that capital, although there may be higher returns to be had in other investments.

The publicly listed REITs also generate growth by investing cash, although many so-called analysts are clearly not aware of this. A lot of those REITs retain 25% of Cash from Operations (CfO), give or take, for reinvestment.

If they invest those funds at a 5.7% ROE, they grow CfO by 1.4%. They can increase this to near 2% with modest leverage. Combine that with perhaps 2% increase in CfO from rent growth and you get a 4% CAGR. This would be reduced by headwinds such as tenant bankruptcies or increasing interest rates.

In other words, such REITs, like the private, cash-only investors mentioned in the quote above, don’t need to care about spreads in order to grow earnings.

What Adding Debt Does

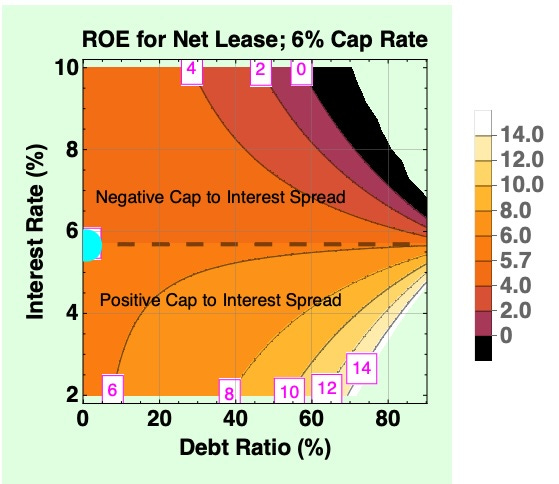

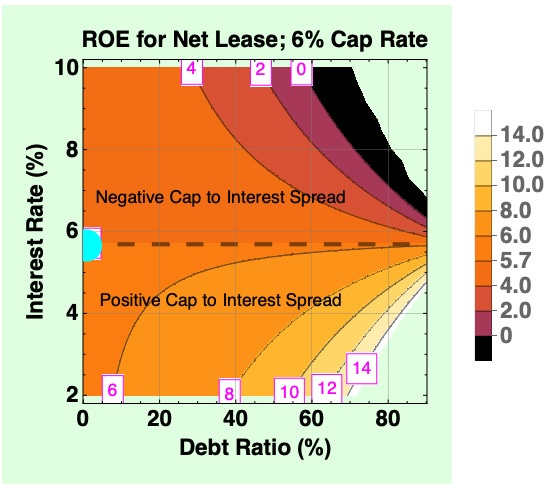

This next plot shows how the ROE for net lease, from the equation above, varies with debt ratio and interest rates for a 6% cap rate. Other property and lease types have the curves shifted downward, reflecting higher non-interest costs, but the overall pattern stays the same.

Here the cyan dot shows the 5.7% ROE one gets with zero debt. The heavy, dashed line shows the 5.7% ROE that corresponds to any level of debt when the interest rate equals the cap rate.

Interest rates below the cap rate (i.e., positive spreads) are portrayed below that heavy dashed line. For a spread of 200 to 300 bps, one can easily get ROE above 10% by pushing the Debt Ratio up near 70%. This is the typical private-equity space.

Of course, up there it does not take a lot of decline in property value to wipe out the equity in a property. We are seeing a lot of that today with office properties.

So you fund single properties (or small groups) with secured debt and in independent LLCs. Then if the equity goes to zero you hand the keys to the lenders, the investors are wiped out, and you walk away to set up a next deal that will keep paying your salary.

That approach turned out not to work so well for the publicly listed REITs. Before the GFC, a lot of them had debt ratios of 60% or more. They were in that private-equity space.

But those REITs could not avoid owning lots of properties and for them handing keys back to lenders has negative consequences. Across the GFC, quite a few such REITs cut their dividends and heavily diluted their shareholders, who often voted with their feet in response.

This had two consequences: There was a general move toward using unsecured debt. This let the REITs push out their average debt maturities, have less debt to roll each year, move up in credit ratings, and reduce interest costs.

There was also a general move toward lowering leverage. If you want a reasonable stock price, you must pay steady and growing dividends. Dividend cuts and dilutive stock issuance hurt that. I discussed the specifics of that evolution for Camden Property Trust (CPT) in my recent article on them.

Look again at the graphic, reproduced just below so you don’t have to keep scrolling back and forth. Having what are now typical debt ratios of 30% (for multifamily REITs) to 40% (for net lease REITs) limits your ROE.

Even for the low interest rates of a few years ago, it was tough to get ROE as much as 200 bps above the cap rate. Today, with cap rates not much above interest rates, a REIT is doing well to get a ROE that is 100 bps above the cap rate.

And when cap rates drop below interest rates, then investors will be in the top part of the graphic. Adding debt will reduce ROE.

Making Money When Spreads Go Negative

There is a wrinkle, though. Such conditions are likely to correspond to inflationary times.

In such times of high inflation and high cap rates, the real-estate game changes to one of gaining from the appreciation in value of leveraged properties. If you own a property that is leveraged at 40%, then 10% of inflation gets you a 17% gain in equity.

At that point you can add debt to restore the 40% loan-to-value. You will pull out 4% in cash while seeing your net asset value (NAV) increase by 10%.

Looking at the plot above, your ROE might be 4% if interest rates are 200 bps above cap rates. Then your overall returns, between the new debt and the cash earnings, will be 8%. And that is on top of the 10% increase in NAV.

But of course even today pretty much nobody in real estate is old enough to have experienced that. And they are fewer every year.

So the question will be who understands it and figures out how to respond effectively. Well, if they have read my work they will be more ready.

It seems likely that AvalonBay (AVB) will do well. A few years ago already they added some debt in response to property appreciation, to sustain a targeted Debt Ratio.

A final note is that sector selection will also matter. Inflation is not the only factor that affects property values.

The Big Picture

Someday I will finish the draft I have of an article explaining why traditional discussions of WACC represent an abuse of Proposition II of Modigliani & Miller. The equation above for ROE can also be derived from that proposition, and in my view is vastly more useful.

Meanwhile, practical discussions such as the above will have to do to make my point.

As an individual stock market investor, you can achieve certain goals with REITs. You can buy ownership in firms whose dividends are very secure and very likely to stay up with inflation, over time. The higher yielding of such REITs now pay mostly between 4% and 5%.

There are only so many of these. I discussed my list here.

Alternatively, you can get more yield by investing in high quality REITs that are less highly valued by the market and somewhat more risky. This is part of what I am doing, while seeking to grow my portfolio to the level where buying more of the first group will make sense.

I share my list of these and discuss them with my paid members. The cost is low and you would be welcome.

Please click that ♡ button. And please subscribe and share. Thanks!

Nice job showing the impact of the interest rate on these investments. The increases in rates are, of course, a response to inflation. As we've discussed in the past, how well REITS handle this opportunity, especially in the long term net lease space, will determine how successful they will be. Some REITS, apartments and retail strip centers have an easier time benefiting from inflation. The triple net lease guys will have to have some serious discussions upon renewal. This is one area that benefits WPC as one-time bumps will not be as great.

On your original Go-Fishing portfolio you suggested you should add some energy midstream companies. You thought a few that met your criteria were EPD, ENB, & KMI at that time. Do you still think this is a good idea? How many would you suggest adding and what weight should they be given in the Go-Fishing portfolio? Also, do you have any other non-K-1 issuing companies appropriate for an IRA account? Thank you!