The broad markets stay flat as risk rises.

My investing is focused primarily in REITs and Energy. These are niche markets often considered treacherous by the ignorant, but also prone to mispricing, which provides opportunity.

My goal is to invest only in firms I know well through deep study. Most of my investments have been in quality companies that were undervalued in the markets. Only a small fraction have been in riskier firms where I see good potential for stronger upside.

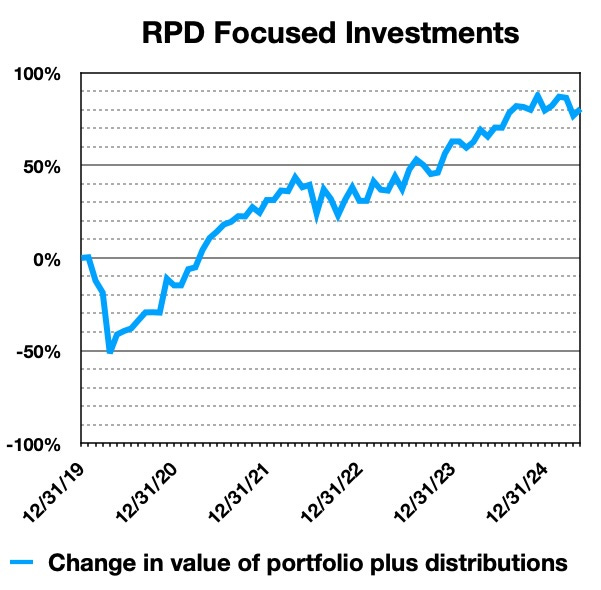

As you can see in the plot above, so far so good. The portfolio market value dropped, like everything, after “liberation day.” But it has come back up a bit and is now 3% below its all-time monthly high last November 30. More importantly, the very secure portion of my dividends would more than cover my spending needs if all paid work stopped.

My subscribers get trade alerts, deep dives into companies, and other useful material. My annual subscribers get direct access to the details of my portfolio.

Now for my focus topic this month.

Market Risks Abound; What to do?

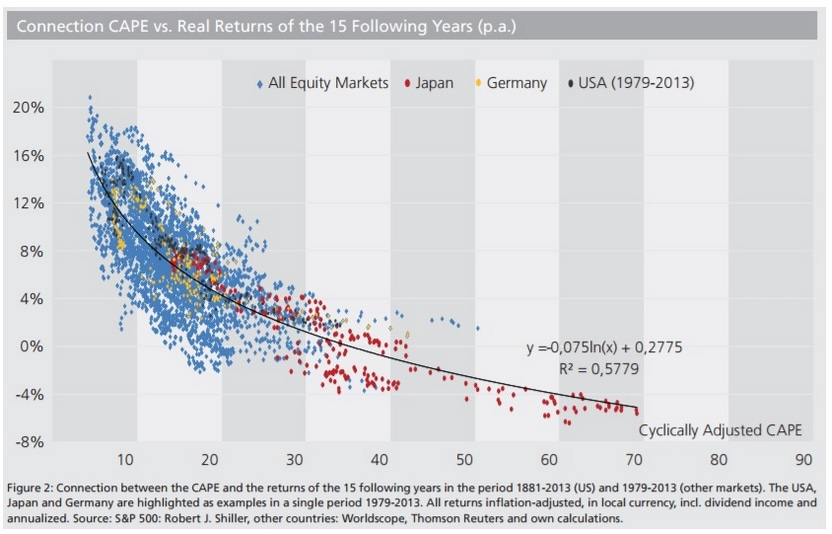

Following the brief correction prompted by President Trump in April, the broad markets have returned to all-time highs. The Shiller CAPE ratio, which divides the stock price by a 10-year backward average of earnings, is at 36:

The only times this ratio has ever been in the present range were the late 1920s, the late 1990s, 2022, and today. The peak in 2022 was stimulated by ZIRP, but today there is no excuse.

I showed a related plot in my last Perspectives, but will show a different one here, taken from the wonderful Lyn Alden.

The past may not be the future, but should inform our expectations. Today the expectation has to be that forward, 15-year, real returns for the S&P 500 will be below 5% and may be below zero.

But should this worry you, if you are in niche markets? The answer: yes because markets this extreme are often associated with economic excesses that must be cured by recessions.

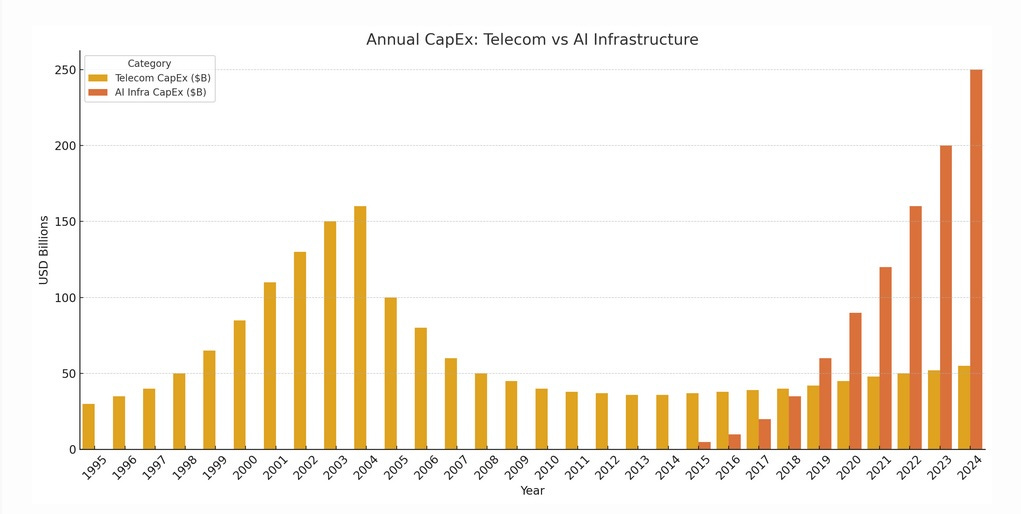

In the late 1990s people were developing devices and building factories based on forecasts of demand for bandwidth. Those people and assets had to find new work after the crash. This drove the recession after 2000.

One angle on where things are today is within the stock market itself. Unprofitable companies are seeing strong returns. From Spencer Jakobs in the WSJ:

What do companies like nLight, Aeva Tech and Ouster have in common?

Aside from snazzy-sounding names, they’re among the 10 unprofitable U.S. companies whose shares were up by at least 200% since the current rally began on April 9. Few money-making ones have done so well.

Analysts at Bespoke Investment Group note that the 858 money-losing companies in the Russell 3000 Index rallied by 36% on average through Friday. By contrast the 500 stocks in that broad index with the lowest price-to-earnings ratios were up by 16% on average.

Spencer goes on to say that this might be OK, given historic behavior. But he also says:

Analysts at Kailash Concepts point out that $16 trillion worth of U.S. companies fetched more than 10 times sales last week—an almost impossible multiple to justify. As a percentage of the entire market, that’s similar to the tech-bubble peak 25 years ago.

The enthusiasm is spreading beyond AI-driven stocks. But it is AI where there may be problems that could affect our investments.

Spencer links this article by Paul Kedrosky. One plot he shows is scary:

The ramp-up in AI Infrastructure spending has been truly massive. Perhaps too large to be sustainable. But scary plots are always easy to find.

What concerns me more is Kedrosky’s discussion of how this is being financed. He says:

I was struck late this past week by Meta's rumored $29b fundraising for a rapid buildout of more AI data centers. The company is supposedly talking to various private equity firms, looking to structure it as $26 billion in debt, $3 billion in equity.

Putting 10% down on a tech investment does not carry zero risk, to put it mildly. What’s more, a lot of such financing is structured as joint ventures or special purpose vehicles, so that the debt does not show up on the balance sheet of the sponsoring firm. But when one of these has financial troubles, the sponsor loses income and may also suffer expenses.

On top of that, some of the funds invested by the providers of private credit come from insurance companies. So your home and life insurance premiums are in part being put at risk in spinning up data centers to satisfy the seemingly infinite demand. Kedrosky says:

And while it all makes perfect sense as financial engineering, this is where the risks start. Why? Because this system creates a powerful incentive loop between structurally overcapitalized insurers, return-hungry private equity firms, and mega-cap companies trying to avoid looking like they're leveraging up. Everyone gets what they want—until something breaks.

The three specific issues that he discusses at more length are the opacity of risk, the ease of overbuilding stimulated by that plus artificially cheap capital, and the duration mismatch for insurers of assets and liabilities.

We are not yet seeing Collateralized AI Obligations. That would be a dead canary in the coal mine.

There are three risk areas here for us as niche-market investors. The first and least important is that our stock prices might drop in a market crash. The second is that revenues might drop enough to force dividend cuts. The third is that a combination of revenue decreases and a liquidity crunch could lead to massive dilution or worse.

Here is what happened after 2000. The 10-year Treasury rate dropped from above 6% in early 2000 to below 4% in mid-2023. That was favorable for REITs. But despite that, AvalonBay (AVB) dropped 25% in price. Their dividends were not cut but did not grow for several years.

Chevron (CVX) dropped 33% but their dividend kept growing, slowly. In contrast, Federal Realty (FRT) and Realty Income (O) did not see a drop in price and did keep growing their dividend, if only slowly.

Later, the GFC was exacerbated by the impact of leveraged Collateralized Debt Obligations. Many REITs had to cut dividends and dilute shareholders. The ones that did had high leverage, with Debt to Gross Assets of 50% or more.

A financial crisis does not look like an imminent risk, but that was also true in the summer of 2008. And by Halloween that year lots of companies were on the ropes for lack of credit availability.

Being a careful and conservative investor, I never like highly leveraged investments. At the moment I like them even less.

And rather obviously I also continue to steer clear of data-center REITs.

The following contains updates throughout; much of it is a repeat of my last monthly update.

My Context

My secure income covers 2/3 of my spending budget. At the moment, the other third comes from various paid work.

The secure income includes social security, a pension, and a collection of annuities. Nearly all those sources have escalators of either 2% or inflation.

My dividends from “Go-Fishing” positions — very secure firms likely to grow dividends at least with inflation — also could cover more than a third of my spending. So if work stopped or when it stops, current spending is covered without drawing down the portfolio.

In the meantime I will use those dividends to grow the portfolio and to provide early legacy spending. That will include some early inheritance funds to the kids each year.

The rest of the portfolio pays additional dividends (though not from all positions). These also will help grow the portfolio.

My portfolio today includes four buckets.

There is an income bucket, which includes mainly “Go-Fishing” stocks. These are from firms that only need monitoring once a year, if that.

There is a “medium-risk” bucket, pursuing gains and income from market mispricing of blue-chips or other quality companies and holding high-yield positions for which I have some concerns about the dividend.

There is an upside bucket, holding small, speculative positions for which I see the potential of gains of 50% or more.

There is an illiquid bucket of long-term, private investments made years ago, valued at my cost. It stands at 13% of the portfolio value.

Most often I hold little cash. But at the moment I have 6.1% in cash. This is discussed further below.

Dividends are the goal but we also know that chasing yield is a losing game. And we know that growth of portfolio market value can be a path to affording larger total dividends.