A subscriber asked why I am not invested in Canadian REITs.

I have nothing against Canadian REITs and have over time invested occasionally. But usually I decline. As my subscribers know, I do own stocks in several Canadian energy companies.

To describe why I have avoided the REITs, I will start with a general discussion.

There are huge differences between private equity and publicly listed REITs. A private equity fund is generally designed to pay out within a few years, and owns one or a few buildings.

If one fund goes bust, that’s the breaks. The LPs lose out and the GP goes off to try to put together a next fund. We’ve been seeing a lot of that since interest rates soared in 2022.

Private REITs may hold many properties, but remain insulated from shareholder panic by having an ability to limit withdrawals. Private REITs also set their own asset values. Mareen Farrell, in the NY Times, writes:

The private REITs are also being scrutinized because of some of their claims. How have they managed to show investors high returns when publicly traded competitors have suffered losses? How can they continue paying out lucrative dividends when they’re not generating as much cash flow each quarter as they’re giving back to investors? What’s their rationale for saying the properties they own are holding their value, when in public markets commercial real estate prices are tumbling?

We have been watching Blackstone’s BREIT kick the can down the road for several years. In the view of some analysts, they have been using DRIP funds from some shareholders to pay the cash dividends going to the others.

These private REITs, like private equity funds, run high levels of leverage. When times are tough they sell assets at a loss, as we’ve been seeing lately. And historically, lots of them ended up bankrupt.

Publicly Listed US REITs

The modern era for public REITs in the US began in 1993. For the next 15 years, most of them behaved like private REITs, in two important ways.

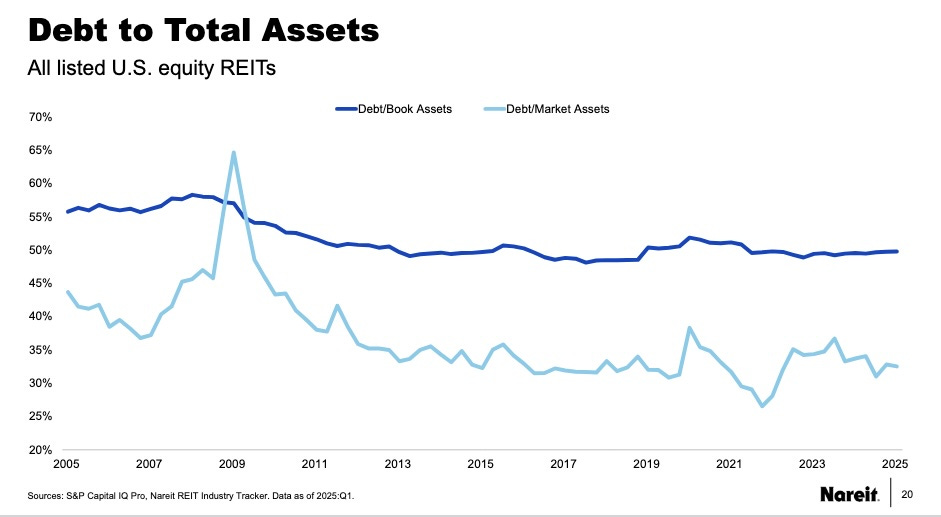

First, many of them ran Debt up near or above 50% of Gross Assets. We don’t have great overall metrics for that; here is what the NAREIT T-Tracker provides:

Since totals are plotted here, these curves are dominated by the largest REITs. Up through 2007, Market Assets (actually Enterprise Value) were overestimated. Book Assets are always underestimated. So the true Debt Ratio lies between these curves.

I have written many times about this risk of high Debt Ratios, recently for example here. The larger they are, the more likelihood that modest revenue drops will force dividend cuts.

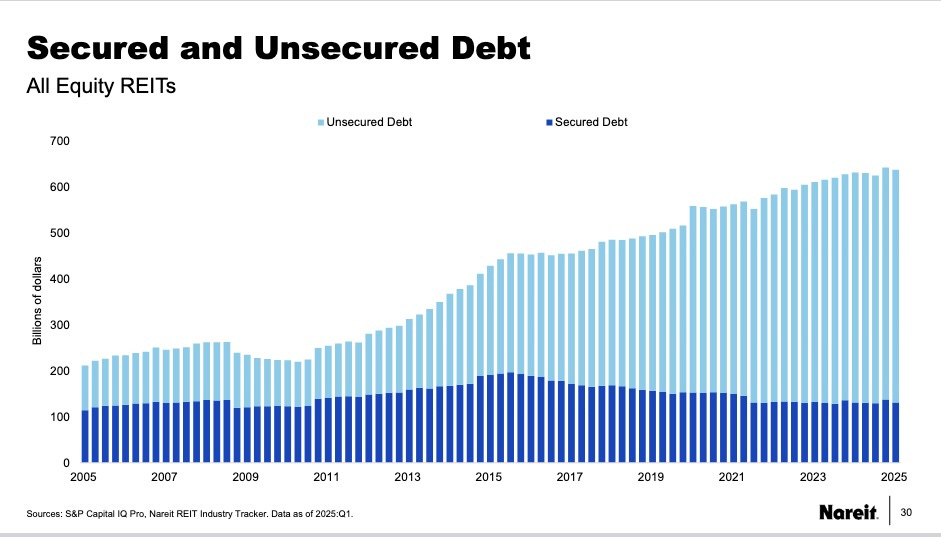

Second, about half of their overall debt was in the form of mortgages (the only option for private REITs).

The big disadvantage for mortgages is that they are short, nearly always maturing sooner than leases expire. Another disadvantage is that they are usually tied to specific buildings, limiting flexibility for dealing with local, temporary issues.

Between high debt and short maturities many REITs were forced not only to cut their dividends, but also to dilute shareholders to raise funds to cover maturing debt. Of course, stock prices cratered. One measure of REIT stock prices, VNQ, dropped by 3x.

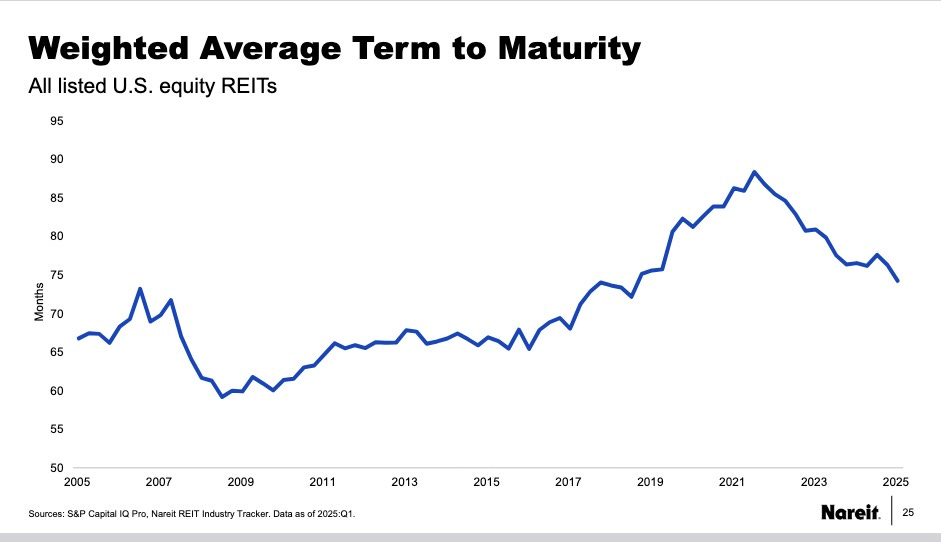

What you see in the graphics above is that public REITs responded to this period by, on average, reducing debt and going to dominantly unsecured debt. This had the impact of stretching out debt maturities:

Stretching out the maturities also implies that a smaller fraction of debt has to be rolled each year. These days good REITs often have available liquidity of 3x their average annual debt maturities. They are prepared to withstand years of bad times.

Not every listed US REIT has heeded these lessons, but nearly all the top ones have. One that did not is Rexford (REXR). Despite having a very low Debt Ratio, their short debt maturities have doomed them to have a much reduced ability to grow cash earnings in near-term years.

Two summary points:

Today, the quality US REITs have low Debt Ratios and long average debt maturities.

In my own investing I nearly always avoid the ones that don’t.

Canadian REITs

One of the enduring irrational aspects of humans is that they cannot learn from others. They especially cannot learn from other countries.

Thanks to having a more stable banking system, Canada did not suffer a financial crisis in 2008. And as far as I can tell, their REITs learned nothing from the US experience.

We don’t have good summary statistics so I will use three examples here.

I did an article on BSR REIT (HOM.U). They have since sold some properties but still their Debt Ratio is pushing 60%. They have a very short debt maturity ladder. Their $150M of liquidity is well below the debt that matures later this year and far below that which matures in 2026.

Canadian REIT RioCan (REI.UN), mainly Toronto retail, also has a Debt Ratio above 50%. But they don’t get a lot of EBITDA from that property value (alleged under IFRS), with Net Debt/EBITDA at 9x. Their average debt maturity is about 4 years and their liquidity at least can cover one year’s debt maturities.

Net-lease REIT Canadian Net (NET.UN) also carries a Debt Ratio to IFRS Assets of about 50%. It is above 60% for their mortgages based on carrying value. Their weighted average debt maturity (by my estimate) is less than 3 years. Their liquidity appears to me to be about half of one year’s maturing debt.

These three are quite typical of what I see in Canadian REITs. The big picture is that pretty much any time I look at the debt structure for a Canadian REIT I turn around and walk away.

It’s up to you what you do.

Please click that ♡ button. And please subscribe, restack, and share. Thanks!

I got burned badly on high debt Cdn REIT's. Another analyst assured me they had it under control on multiple occasions. They did not. I've since reduced the balance of my Canadian REIT exposure to two small positions, and the market will hopefully offer up a chance to dump those too without taking a heavy loss.

BUT, I have taken that bitter lesson and applied it to all my holdings.

Thanks forvtjis exposé. I did not quite get what happened to REXR. Low cash to cover debt maturities in the near yerm? Are its risks priced in now? Or is there a risk of divi slashed?