There is blood in the streets, figuratively speaking, in miners of Platinum Group Metals (PGMs). Some examples:

The Stillwater Mining Company (SBSW) has announced plans to lay off hundreds.

Reuters reports that Northam Platinum (NPHJ.J) CEO Paul Dunne believes that

South Africa's platinum mining industry has entered a phase of irreversible decline as producers struggle with low prices and demand suffers from the rise of battery electric vehicles,

The Wall Street Journal covered the price crash last November, quoting Tom Price, mining analyst at Liberum Capital: “The scale and duration of the [PGM] price fall—together with the subdued macro-backdrop is enough to deter investors in the mining space.”

Newzroom Afrika reported the pending loss of thousands of jobs across the major firms in the sector.

What’s more, metal prices have not been improving. One can own physical platinum (Pt) and palladium (Pd) by investing in Sprott Physical Platinum & Palladium Trust (SPPP). Here is their self description:

The investment objective of the Trust is to provide a secure, convenient and exchange-traded investment alternative for investors interested in holding physical platinum and palladium bullion without the inconvenience that is typical of a direct investment in physical bullion. The Trust invests and intends to continue to invest primarily in long-term holdings of unencumbered, fully allocated, physical platinum and palladium bullion and does not speculate with regard to short-term changes in platinum and palladium prices.

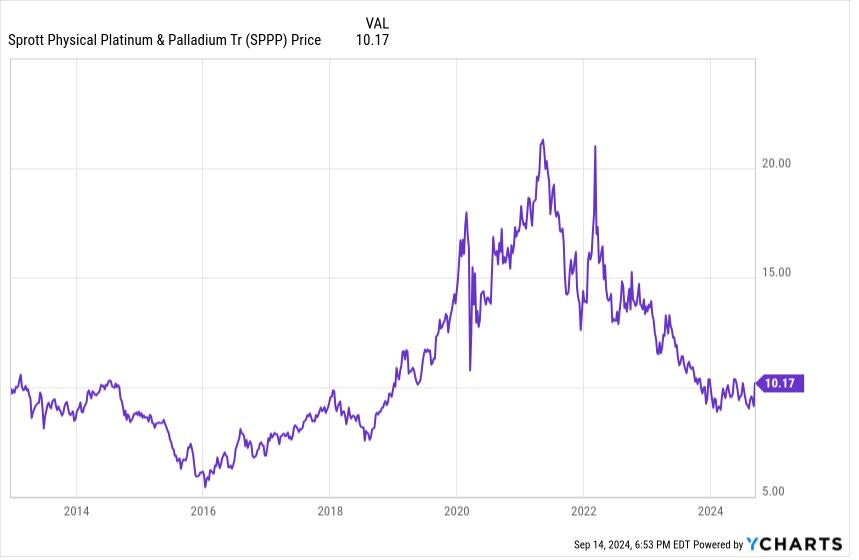

Here is the price action of SPPP:

The price is back where it was a decade ago. It certainly seems that today’s pricing will only support further troubles in the industry.

Of course, the simple narrative has been that there will soon be no vehicles with internal combustion engines (ICEs) because all vehicles will be battery-electric vehicles (BEVs) and that this will permanently destroy demand for platinum and palladium for catalytic convertors. But simple narratives are always wrong, though it is not sufficient to invest against them without thought.

So let’s look into the PGMs and seek to apply some thought to their future. After some introductory context, that will be my subject today.

Why Mining, Why PGMs?

At Focused Investing, my primary emphasis is REITs and the oil and gas industry. There are two big reasons for this. They are both areas that my decades of experience leaves me able to understand. And they are both niche markets where one can hope to find inefficiencies in stock pricing.

That said, the really good opportunities in both those areas are limited. Having a third area has long made sense.

The other natural area for my background is mining. I even made some money a few years ago on Copper Mountain Mining Company, long since merged out of existence. But that involved a strong element of luck too.

The reason I did not keep going was China.

The history of debt-driven expansions in countries unable to resolve (or maybe even identify) bad debts is clear. They eventually enter a long period of slow growth and social challenges. I’ve expected China to end up there for more than 5 years, and especially since some insightful guest commentary in Barron’s in 2019.

This is problematic for mining. China utterly dominates the global iron ore market and is a huge component of the copper market too. A lot of those two has related to their vast and unsustainable construction activity.

China is also a big player in a lot of other metals, notably lithium. So if you foresee possible huge changes in Chinese demand for these things, it is hard to know how to assess the miners.

I recently became aware that China plays a relatively minor role in the PGMs — platinum, palladium, rhodium, osmium, iridium, and ruthenium. There is more below on their uses, the largest of which is for catalysts for industries using ICEs.

Now if you have been reading the media and listening to politicians, all vehicles will very soon be BEVs. But most of those seekers of clicks and votes have no technical background and no basis for making judgements about what is feasible and how long it might take. If you know a bit of science and engineering it becomes clear that near-100% adoption of BEVs requires a level of expensive infrastructure far above what now exists in the US and Europe, let alone Africa and most of Asia.

A second car that charges in an urban garage, for the minority who have garages? Sure. An only vehicle in rural Montana, or in the Congo? No way.

Demand for PGMs may not return to its peak levels, but it will endure. And the contribution of catalytic convertors for ICEs will be a lot larger than the pundits would have believed.

So combine blood on the streets among the producers with a demand picture that has been misunderstood to the negative. One can smell potential opportunity. Let’s look a bit deeper.

Supply and Demand Drivers

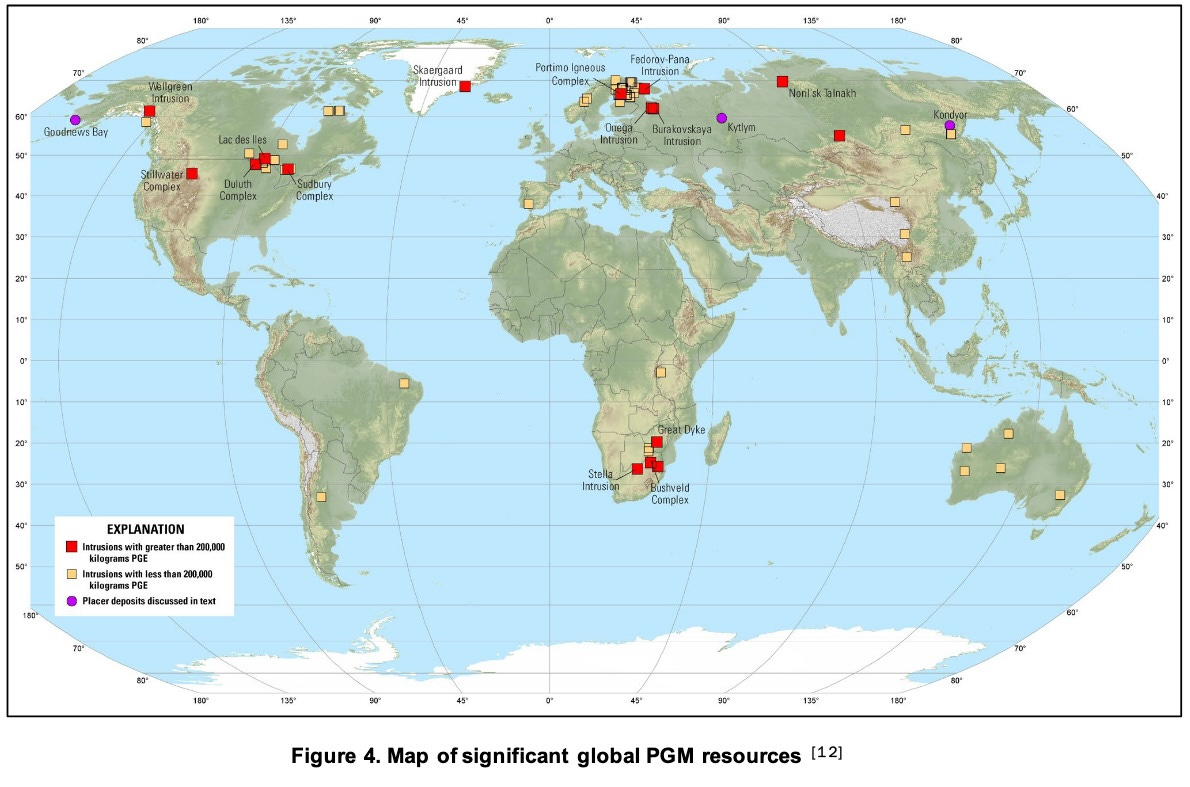

Known resources are widespread. Here is a nice map of known global resources, from Energy.gov:

The red squares show the big deposits. Notable regions include South Africa, North America, Northern Europe, and Russia.

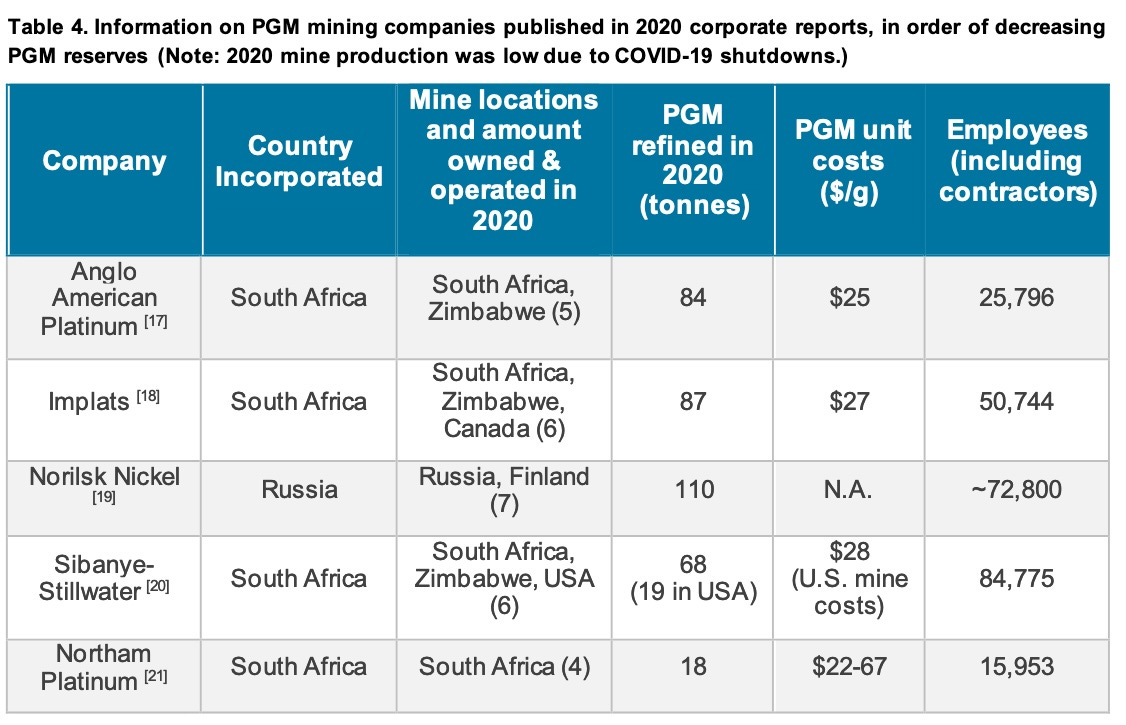

Here are the five producers with the largest reserves, according to the USDOE:

One thing that seems clear is that if you seek to invest in a relatively large mining company, you are stuck with South Africa. This of course brings political risk.

Costs are higher today. Anglo American Platinum reports PGM units costs and All-In Sustaining Costs (AISC) near $1,000/oz. This translates to about $36/g.

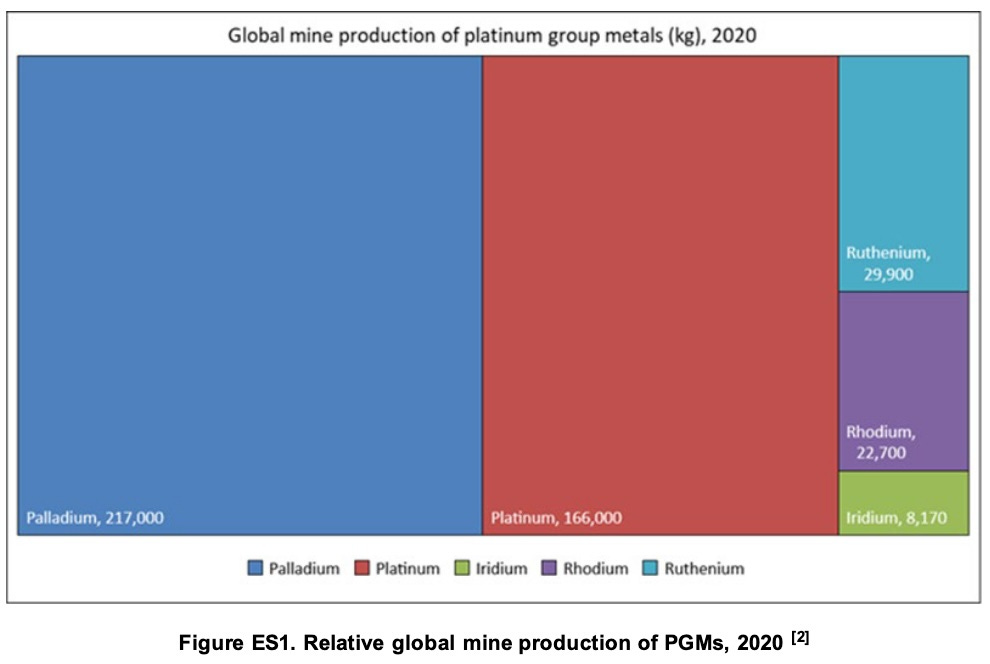

The PGM supply is dominantly platinum and palladium, with lesser amounts of the others. At the time, 2020 was a down year because of Covid. Platinum production today, though, is comparable to the values shown in this 2020 plot:

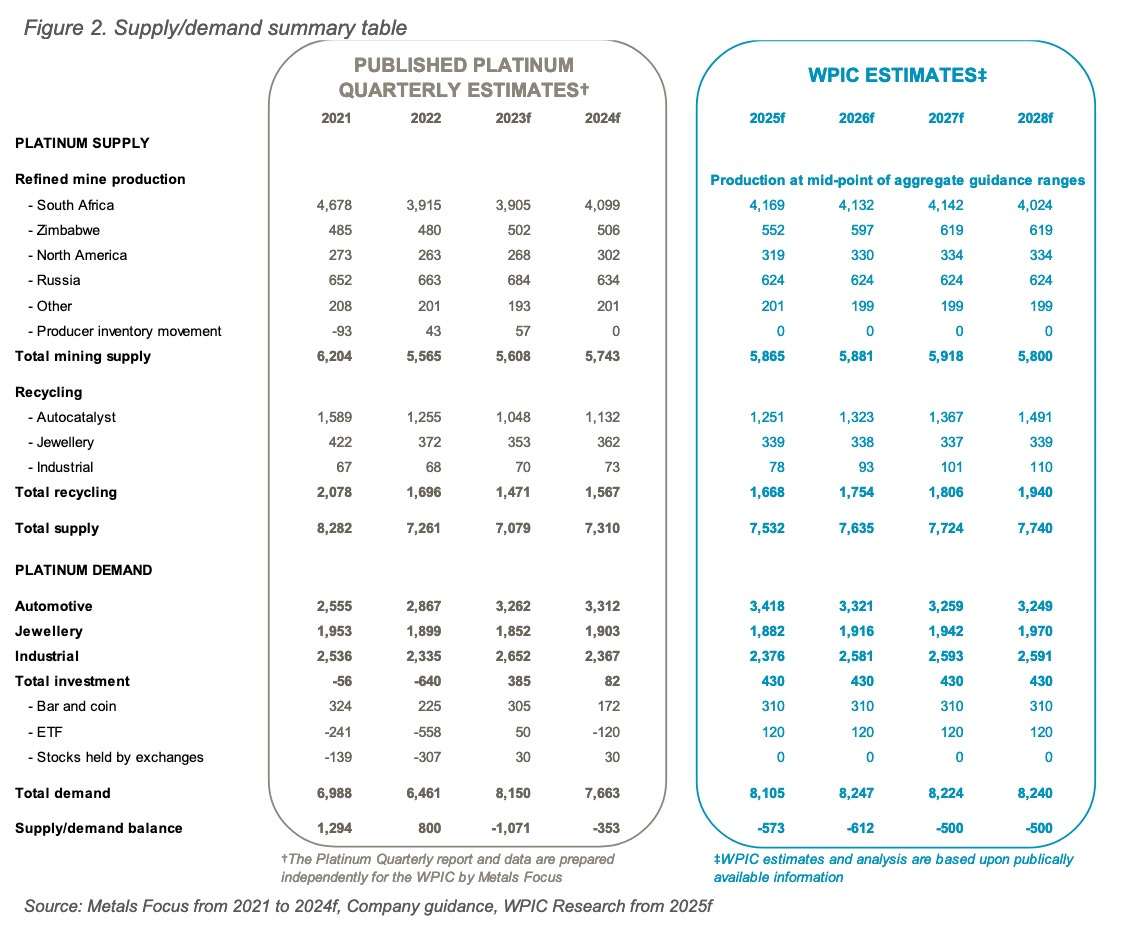

The following table from the 2024 two-to-five-year platinum outlook by the World Platinum Investment Council (WPIC) provides more information. The gray part covers 2021 thru 2024. The blue-green part projects the next four years. Numbers are thousands of ounces.

You can see that South Africa provides about 2/3 of mined supply and half of total supply. Recycling, dominated by autocatalysts, provides about a quarter.

Demand for automotive applications, jewellery, and industrial uses are all substantial. In contrast, investment demand runs near 5% of supply.

The bottom row is really important. Platinum entered a period of structural deficits in 2023 that is projected here to continue at least through 2028.

But that is not the full story. Stay tuned.

Response to Losses?

The WPIC also had this to say in their 2024 two-to-five-year platinum outlook, from January:

Primary supply forecasts have only been reduced by ~2% since our previous reports to reflect public announcements from PGM miners. However, we simultaneously estimate that 25% of PGM mined production [35% ex-Russia] is loss making at depressed spot prices while noting that most production guidance does not reflect financial reporting to December 2023. This suggests the potential for more downgrades.

Despite an upcoming national election in 2024, most South African producers are already initiating some form of restructuring … The pace at which miners have responded, reiterates that PGM prices are too low and raises the prospect of supply side risks.

Here is how they connect the dots. Here are key statements in the related Platinum Essentials report:

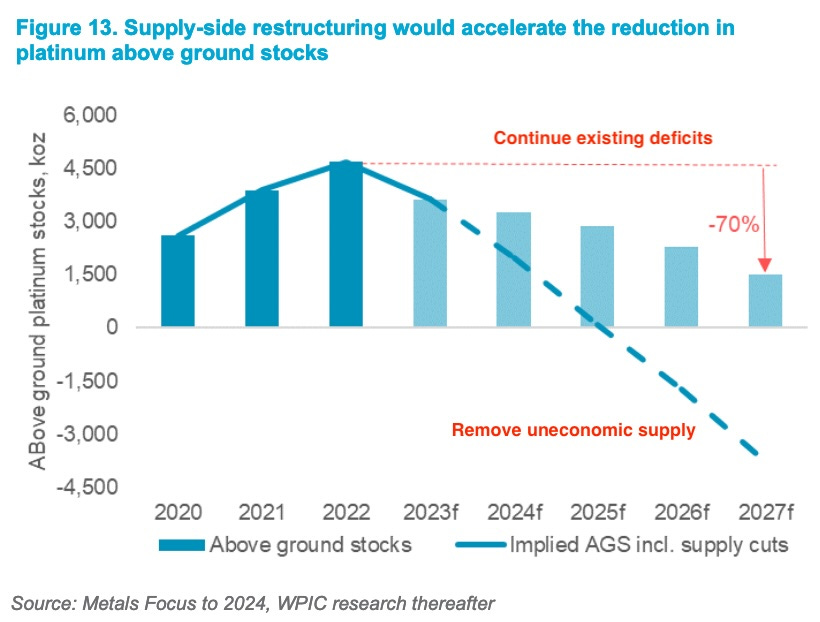

Without supply cuts, WPIC expects platinum deficits to underpin a 70% reduction of above ground stocks from 4.6 Moz to 1.4 Moz. The determination of above ground stocks has caveats, but above ground stocks would theoretically erode by the end of 2025f (Fig. 13) if 1.3 Moz pa of loss making Pt supply were placed on care and maintenance.

Here is their Figure 13, perhaps the most important for our purposes today:

If miners just increase debt to continue at 2023 production, then the above-ground supply of platinum would last until nearly 2030. But if they fully shut off uneconomic supply then by a year from now the above ground stocks will be depleted. One would then expect platinum prices to soar.

WPC adds this note about palladium:

Palladium’s supply side risks could be deemed greater than platinum’s. We estimate that idling loss-making assets would reduce palladium supply by 1.2 Moz per annum which keeps markets in a deficit rather than our underlying forecast that supply will enter a surplus from 2025f.

And of course the miners are not standing still, as was summarized at the start of this article. Here is a specific example from Anglo American Platinum in their mid-year 2024 report:

The company responded decisively to an uncertain macro-economic and a low PGM price cycle by restructuring the business in pursuit of operational excellence, increased levels of productivity as well as ensuring cash-generation capabilities (value over volume), while maintaining the future growth optionality of our operations (pathways to value). These initiatives include our sustainable cost-out programme that is expected to deliver R10 billion annual cost savings from operating costs and stay-in-business capital from a 2023 baseline. Approximately R4.7 billion has been achieved in the first half of the year

That R10 billion in savings is $570M. That is about 40% of their EBITDA, which is obviously significant.

Financial Status

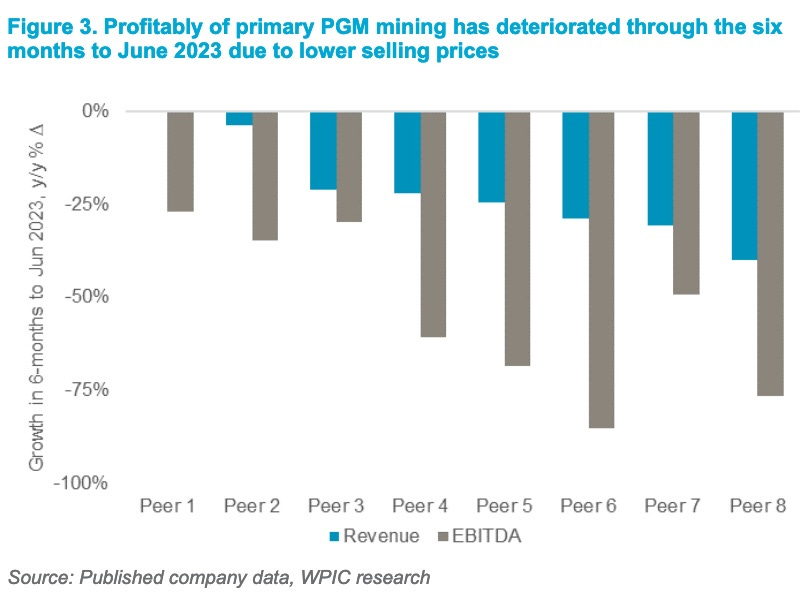

Remarkably, the major PGM miners have not been taking losses, at least through H1 2023. We see here that EBITDA dropped but not more than 100% for the 8 peers examined by WPIC:

These mines do have large fixed costs. This is why EBITDA drops a lot more than revenue.

Since June 2023, platinum prices are relatively flat and palladium prices have dropped about 20%. At the same time, cost reductions have been underway. Anglo American saw its EBITDA drop about 15% in H2 of 2023, then come up about 9% in H1 of 2024.

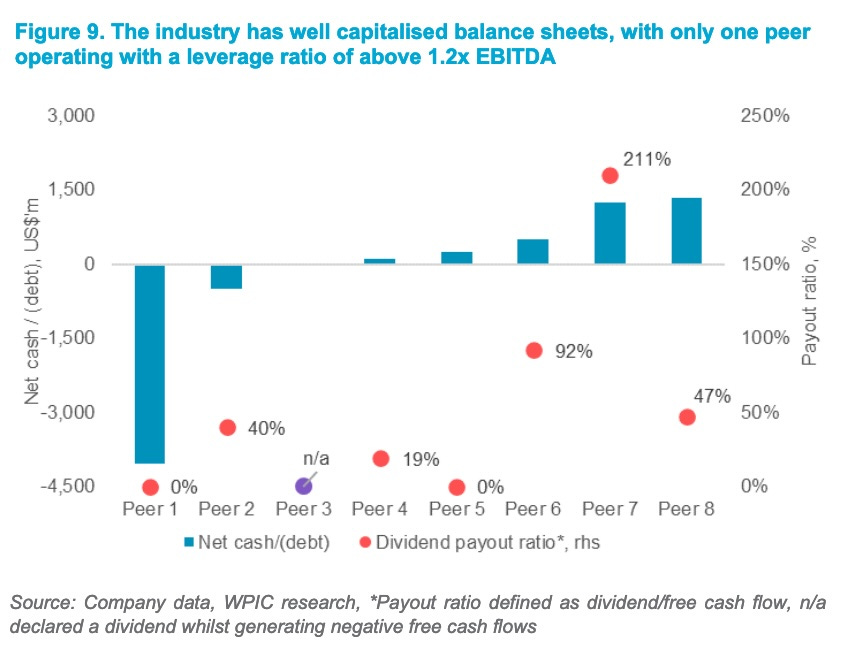

What is more, these companies used the great prices in 2021 and 2022 to bulk up their balance sheets and most of them have zero net debt. Here is where that stood at end of 2023 (again from WPIC):

The upside here is that most large PGM miners will have no problem surviving the present period of low prices. The downside is that they have the option of sustaining uneconomic production if they so choose.

But, as detailed above, it looks like most of them are pulling back.

Takeaways

In my view the above information supports a few conclusions.

Big moves for PGM miners likely will require substantial depletion of above-ground stocks of platinum. Those stocks will last one to five years longer.

Those miners are by and large pulling back on production. So the change seems likely within a couple years or so rather than five.

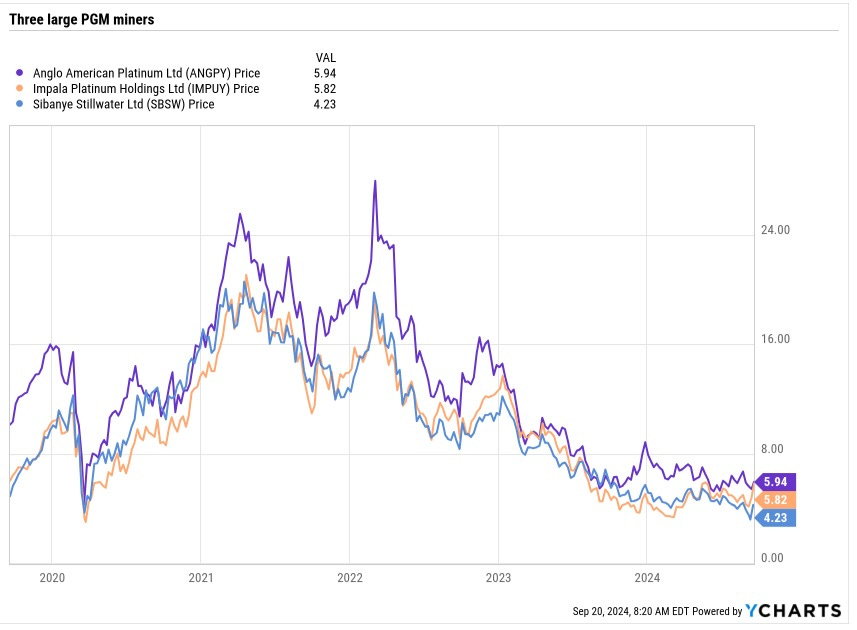

Prices on the stocks from the big miners are depressed. Here are Anglo American Platinum, Impala Platinum, and Sibayne Stillwater, with Market Caps of $9B, $5B, and $3B, respectivtly:

These are all down 4x, or close to it, from their highs. Even though they may not get back there, there is lots of upside whenever the cycle turns.

So there is no need to look for very solid gains in some highly indebted junior miner. That is not a game for careful, retired investors like me, anyway.

I see no hurry to invest. But if you prefer to get in early, as I do, then within the next year could be good.

All that said, one has to remember this: PGMs are commodity natural resources. While cycles are assured, timescales are not!

Please click that ♡ button. And please subscribe and share. Thanks!

Hi Paul, as you pointed out investing in the PGM mining space is almost inextricably linked to investing into South Africa due to the Bushveld complex, a remarkable "geographic feature". Investing into SA comes with the classic EM risks which are not to be underestimated. As an example during 2018/9 the end of the Zuma years the risk of nationalisation of the mines was very real. If the current president is turned or the GNU dissolved that risk arises again. The Mining Co. hold a worrying place in the minds of the "mining class" due to the history of the country. The Marikana massacare brought this to the fore not long ago. The mines have over the past decade had to contend with very severe energy restrictions. That all said, over the long term, the ZAR should continue to depreciate against the USD decreasing ZAR based costs.

In addition to the above, how do you consider the risk either a replacement material or synthetic platinum?

That all said, South Africans are wonderfully resourceful and well versed in navigating a tricky local environment. The country also has limited financial options and cutting the miners off would be a real shot to their own foot. Lastly, a trip to visit your investment would a joy.

Thanks Paul. Super interesting.

As you say in your note, one has to be comfortable with South Africa. Curious to know if you came across any ETFs which might consider as a proxy? (e.g., to mitigate some of the currency risks of the South African Rand or the friction of SA markets)