Beware of economists with their idealized systems.

I read an article today that offers a quasi-Austrian-school view of interest rates and inflation, making mistakes I see often. Having no desire to chew on the author as such, the following is anonymized. This just provides an opportunity to counter a number of views with which I disagree.

The article starts with a very common story about the onset of recessions resulting from consumer drawbacks. The idea is that increased financial stress, often but not only caused by inflation, leads consumers to pull back spending and that this sends the economy into a recession. One sees this story all the time, but it seems to me to have rarely if ever been correct.

None of 1999-2003, 2007-2008, or 2020 were periods where consumers quit spending because of inflation. The first two were driven by the collapse of economic excess and in 2020 governments substantially suppressed economic activity.

I don’t think the early 1990s recessions were of that type either, as that period was not inflationary and one issue was excessive real estate speculation. And if you go back to the early 1980s, the recessions did not come until the Fed created a (badly needed) liquidity crisis, causing a sharp contraction of debt and therefore M2.

I’m less sure about the mid-1970s, although common lore blames OPEC.

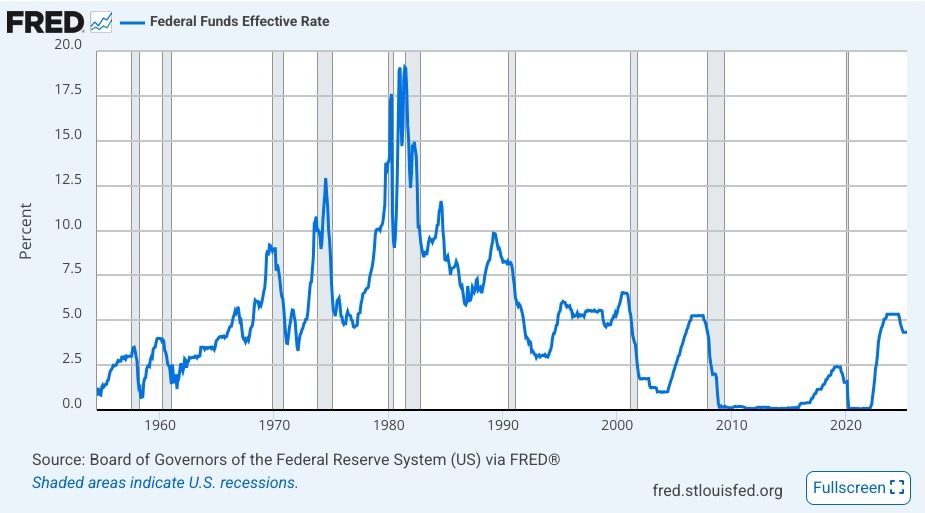

Until the 2020s, which we take up below, a common element for recessions has been that the Fed has raised short-term interest rates before the onset of each recession. This goes back at least to the mid-1950s:

The term “financial crisis” is often misused. Properly, in my view, it should refer to a period when almost no one can borrow money from banks, no matter how good their credit or collateral. Gary Gorton describes the dynamics very well in his “Misunderstanding Financial Crises: Why We Don't See Them Coming.”

The issue with financial crises, of which 2008 is really only the modern example in the US, is that when they hit there are legitimate reasons to fear economic collapse. The inability to access new debt can readily trigger massive defaults and bankruptcies, and a complete breakdown of the financial system.

There were a lot of such crises, often local, earlier in US history, and there have been any number over time worldwide. Now wonder governments have always violated their own laws, if needed, to support the continued functioning of their financial systems.

Also, the standard Austrian description of the need for and purpose of recessions has not stood up well lately. The Austrian view has been that many bankruptcies have ensued when interest rates were raised, because those businesses represented misallocation of resources and needed to die. But that did not happen in the 2020s. Interest rates went up dramatically and the US had no recession.

Why? Because until 2022 when the Fed increases interest rates they did so in a way that created a liquidity crisis, by reducing reserves. It was lack of liquidity that caused the recessions, in my view.

After 2021 the Fed changed its approach. They raised interest rates in a way that sustained ample liquidity by sustaining ample reserves. And we saw no recession. My interpretation is that many companies can adapt to higher interest costs, but a much larger fraction cannot adapt to an outright inability to roll debt.

[This is a common-sense notion, not a surprise in retrospect. In my view it is typical of the Austrians to be so lost in their theoretical systems that they miss ways that reality might differ. And to be fair, such blindness is not unique to the Austrian school.]

There is also a disconnect about debt. The article wants to blame buybacks for driving up debt and increasing corporate vulnerability. It shows buybacks increasing over the past 30 years. But the overall private economy has become less leveraged, as you can see here:

You can find the decline in non-government debt over recent decades in the US discussed in many places.

The article proceeds to cite and otherwise blame governments for increasing their debt, which makes sense. It quotes Ray Dalio warning of a US Debt Spiral.

Well, perhaps. But to my mind it is far more likely that the US will inflate away their debt. Over time, this has been the solution for most countries with their own currency.

People may scream at first, as they did after 2020, but across time and the globe people and economies adapt to inflation. (This is not to say that there are not large negative impacts.) Inflation drives down the real value of past debt while increasing nominal GDP.

Then there is the argument that technology is deflationary. This is the flip side of arguments that increased prices for one thing, say oil, is inflationary. We see such comments all the time. And they would be true if the economy were otherwise fixed, with no one adjusting their spending in response.

But those arguments are not true. Human wants and human adaptability are both endless. If TVs get cheaper, people want better ones or computers. If gasoline gets more expensive, people cut spending to make ends meet. What matters for price inflation, in modern economies, is what happens to total debt.

Finally the article mentions AI. At the moment the AI hype is deafening. But I remember when computers were about to replace many jobs and devastate the economy. I also remember when the internet was going to do the same thing. Here we go again.

Please click that ♡ button. And please subscribe, restack, and share. Thanks!

I know a British marxist-inspired economist who believes that economic booms and recessions are ultimately driven by the amount of (corporate) investments, and that corporate investments are mostly driven by expected profit returns.

He criticises what he sees as "the Keynesian school" that believes that consumer spending is driving force of recessions. He doesn't mention it, but I believe in his view consumer spending only has impact to the degree it influences expected profitability.

I didn't know boo about the Austrians and appreciate how you've presented the information and your own thoughts! I do know that "idealized systems" pose problems in all disciplines, and it seems to me that your skepticism is warranted and based in evidence. On a more mundane note, I noticed that good ole Algonquin had a surge today and wondered if it's a mere, idealized blip. Another possible idealized move up came from STHO, which some of us poor souls remain invested in (but only a small tranche). I know these companies aren't in your portfolio, but I believe that at least one was, sometime in the ancient past. Maybe other members have opinions they'll share.